Today, guest columnist Zach Grudberg begins “The Song Remains The Same,” a column focusing on great, yet underappreciated songs by canonical musicians. Any musician/band is fair game (as long as the song fits the above-mentioned criteria; I’m not planning on regurgitating why “She Loves You” is the perfect pop song for the hundredth time in the history of print), so feel free to suggest some you feel would be a fruitful topic for discussion. At the end of each article I’ll post some info and links related to the music discussed in the that week’s column.

———————————-

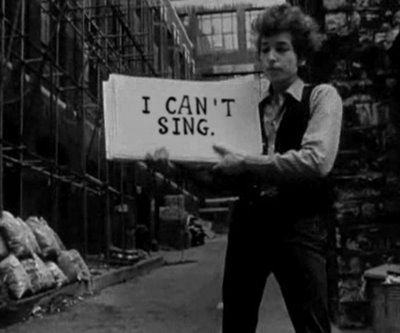

Whatever the costume Dylan wishes to don – folk troubadour, confessional songwriter, country crooner, tough bluesman, Beatnik rock and roller – his music always carries with it a vital understanding of roots music. The best folk songs sound modern but they also sound like they could’ve been written a hundred years ago. And that is the crux of Dylan’s music; that essence which places it not in a time period or genre but into the larger continuum of the American music tradition.

If any song by Bob Dylan fully exemplifies the above, it’s “Blind Willie McTell.” It was recorded for but curiously left off of 1983’s Infidels, an album warmly received for its return to secular themes after Dylan’s much-reviled gospel period. Religious overtones still find their way into the subject matter however. The version I’ll be discussing in this article is actually a demo; a take that Dylan recorded with a full band has yet to be officially released. Since I don’t own a would-be illegal copy of it, the full-band version will remain untouched in this article. Dylan aficionados being the notorious bootleggers that they are, (I’m not kidding; they were actually the first fan base to circulate bootlegs on a widespread level starting in the 60’s) the song found its way onto unofficial tapes and quickly became of Dylan’s most popular compositions among his fans and colleagues. The man himself never performed it live until he heard a cover by the Band, but since then it has become a concert staple for the “Never Ending Tour.”

So what makes “Blind Willie McTell” such a powerful song that deserves to be heard outside the circle of Dylanologists arguing over who exactly is “Einstein disguised as Robin Hood?” It’s the very subject matter of the song itself; a damning of America’s troubled past and the redeeming music that emerges from those who have suffered the most. Dylan imbues the song with a sense of timelessness in two important ways. First, he adopts the melody from “St. James Infirmary Blues,” an American folk song about a man who finds his lover lying dead in a hospital as a result of their morally questionable actions. This already connects the song to the rest of Americana by doing what people have been doing for hundreds of years; taking old songs and changing them. (“St. James Infirmary Blues” is itself adapted from an an English folk song known as “the Unfortunate Rake.”) As I’ll discuss later, it also ties into the larger theme of the song itself. The second thing Dylan does to make the song mythic in scope is weaving the narrator’s perspective in and out of different periods American history. This conveys to the listener that the cycle of pain and seeking relief from that pain through music is not unique to any time; it is something universal to the American experience.

Although not an outright gospel tune, religious imagery plays a key part in the lyrics. It becomes a framing device that Dylan uses to chastise America’s various ills in a manner similar to the way the narrator of “St. James” laments the sins that’ve brought their lover to death. After a piano intro by Dylan (again adopted from “St. James”) accompanied by Mark Knopfler on 12-string, the song begins:

“Seen the arrow on the doorpost

Saying, ‘This land is condemned

All the way from New Orleans

To Jerusalem.”

I traveled through East Texas

Where many martyrs fell

And I know no one can sing the blues

Like Blind Willie McTell”

The last couplet ends each and every verse, tying together scenes of Civil War (There’s a chain gang on the highway/ I can hear them rebels yell), debauchery (There’s a woman by the river/ With some fine young handsome man/He’s dressed up like a squire/Bootlegged whiskey in his hand”), slavery (See them big plantations burning/ Hear the cracking of the whips) and death (“Hear the undertaker’s bell”). Dylan’s vocals grow louder and louder by the end of each refrain. At the collapse of the last verse he’s practically howling the words, giving one of his best vocal performances. It is here where the song gets its name, but why is Blind Willie McTell mentioned at all? Again, Dylan is tying the song and the subject matter to Americana at large. The blues was developed in the Mississippi Delta, an expression of pain molded by the experiences of living in Jim Crow America. Blind Willie McTell is revered as one of the best of the original Delta blues singers (Dylan obviously thinks so) and thus the metaphor now becomes clear. Amidst the evils of America, it is in the music created by those affected that Dylan finds redemption. Even though he is blind, Willie McTell expresses the pain of living in America in a more beautiful and better way than most of those with sight. Another telling aspect are the last days of the blues singer’s life; after becoming a preacher, he never sang the blues again. But America is not yet at peace. Religion enters the lyrics again during the last verse:

“Well, God is in heaven

And we all want what’s his

But power and greed and corruptible seed

Seem to be all that there is

I’m gazing out the window

Of the St. James Hotel

And I know no one can sing the blues

Like Blind Willie McTell”

It is here that we find another link to “St. James Infirmary Blues.” St. James was a real place that opened as a hotel in New Orleans in 1859 and was later converted into a military hospital by Union troops during the Civil War. The lyric serves not only as a nod to “St. James” but also as a tie-in to the Civil War and the larger themes of death and the decay of America. Dylan’s last rendition of the refrain ends on a hopeful note, despite the apocalyptic overtones of the rest of the song. Even as the narrator is in bed dying at the St. James Hotel, he still manages to find meaning in Blind Willie McTell’s music. Whether the rest of us can find similar redemption in anything is the real question the song poses. It’s one that people have asked themselves throughout our nation’s history and is a vital part of what makes the song so haunting. Astounding for a piece of music that might’ve been thrown away forever, “Blind Willie McTell” is surely deserving of the accolades usually reserved for Bob Dylan’s more popular tunes.

“I have to think of all this as traditional music. Traditional music is based on hexagrams. It comes about from legends, Bibles, plagues, and it revolves around vegetables and death. There’s nobody that’s going to kill traditional music. All these songs about roses growing out of people’s brains and lovers who are really geese and swans that turn into angels – they’re not going to die. It’s all those paranoid people who think that someone’s going to come and take away their toilet paper – they’re going to die….traditional music is too unreal to die. It doesn’t need to be protected. Nobody’s going to hurt it.” – Bob Dylan

—————————————————————————————

You can find “Blind Willie McTell” on the Bootleg Series Volume 1 – 3 (Rare and Unreleased) 1961-1991, an officially released compilation of various Dylan bootlegs collected over the years. “St. James Infirmary Blues” has been covered by countless artists over the years, but the version that made the song famous was Louis Armstrong’s 1928 recording. The White Stripes (also big fans of Blind Willie McTell, to which their first record is dedicated) have also released their own take on this classic folk song. Blind Willie McTell himself recorded around 70 songs over his lifetime and they are all available on various compilations. If you want to to dive right into the deep end, you get all three volumes of his Complete Recorded Works from Document Records.

“Blind Willie McTell” – Bob Dylan http://www.wat.tv/video/bob-dylan-blind-willie-mctell-1q85w_2gh7d_.html

“St. James Infirmary Blues” – Louis Armstrong http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oXMx8OW32Bs

“St. James Infirmary Blues” – The White Stripes http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oXMx8OW32Bs

“Statesboro Blues” – Blind Willie McTell http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fnWxZtI3ONY